— Chapter Eleven: The Return of Mouse —

Comedy of Errors may also be purchased from Main Point Books in Wayne.

In early November, Stewart was already dreading his next co-op assignment, which he loathed more than the classes he was attending. His relationship with Clara had deteriorated and he was struggling through trigonometry and chemistry, but his class in semantics surprisingly sparked his interest, as did an introductory course in psychology taught by a professor who seemed to understand Stewart’s disabilities. Meanwhile, Stewart’s confrontation with his mother had inspired him to create a wacky series of darkly comical strips based on his parents who many times seemed to possess little common sense or any ability to function logically.

So as to not completely reveal the source of his humor, Stewart portrayed himself and his family as mice, drawn in a style that differed from the one he used on the fliers he distributed in high school. Unlike his mother, the mother mouse was quite heavy, and wore pearls and high heels, but the father mouse was bent over when eating, reading a book or playing solitaire. The child mouse was also portrayed to be 10 or 11, rather than 19. The initial panel of his first strip depicted the child mouse peering from behind the title, Mouse, spelled out in large block letters with his name hand-printed under the title.

In the second panel, the family is having dinner and mother mouse is shown erect and eating properly while father mouse is hunched over his plate with his eyes facing his meal. A balloon over the child’s head reads, May I be excused? I’d like to take a bath before heading out with Eric to a movie.

In the third panel the reader can see a shadowed profile of the child mouse preparing to depart, as the mother is facing the viewer. You’ve just had dinner, Stewart. Remember, you must wait an hour after you eat before you bathe.

And why is that? asks the child mouse, looking down with a sarcastic grin towards his mother’s silhouetted profile.

Because you can get cramps after eating and drown. I’ve told you that a thousand times.

In only two inches of water? questions the child mouse, who’s not visible to the viewer as mother mouse addresses Stewart in a full view.Don’t argue with me, Stewart. You can take a shower, but not a bath. May I remind you that your aunt knew a boy who drowned in less than one inch of water, so just do as I say, and don’t question me again on this subject.

Father mouse looks up from his plate in the final panel with his fork full of food and says, Do as she says, son. But, please let me take a bath first before you shower, so I can test her theory, and I very much hope that she proves to be correct.

In the cartoon, Stewart used his own contemptuous response to his mother’s often-spoken narrative to convey her naive view of science and the world in which she lived. He then provided his father’s fatalistic approach to dealing with his wife, and the resignation he accepted for his diminished position in the family dialogue, as well as his viewpoint that death would be a welcome alternative to living.

Stewart believed that if his mother saw the cartoon, she wouldn’t recognize herself, or understand the ironic nature of her statement. She listened to old wives’ tales and never questioned the stupid opinions of people of supposed authority. People who were wealthy or who came from good families were considered “smart”and those with advanced degrees or who attended the right school or colleges were better people than those who attended public schools and attended state colleges. Although her perspective may have been right to some degree, she never chose to explore beyond the surface when making her evaluations.

In Stewart’s second cartoon, father mouse is shown standing in front of the “Mouse” logo, explaining to his wife and child that on Tuesday the large amount of money he’s been promised will pay the rent as well as settle all of the family’s debts.

The second panel, inked entirely in black with a single rectangle of white light shining through what appears be the blinds in a window, has no copy.

The third panel depicts the same image, but is shown in daylight with a red caption block at the top-left that reads, “Monday.”

The following panel is again black, with no light showing, while the fifth panel reveals father mouse sitting at a bar, buying drinks for a group of male mice who surround him as he appears to be drawing. Two empty shot glasses and a beer are to his left.

The sixth panel shows father mouse walking down the street with his shirt untucked and his head tilted back with a bottle to his mouth. In the left-hand corner, a red block states the day, “Tuesday.” Panel seven is a closeup of father mouse silhouetted against a gray background, positioned inside the open door frame of his family’s apartment. His head is in silhouette, but his eyes are left white and knitted in anger, with red veins crossing them. There is no copy.

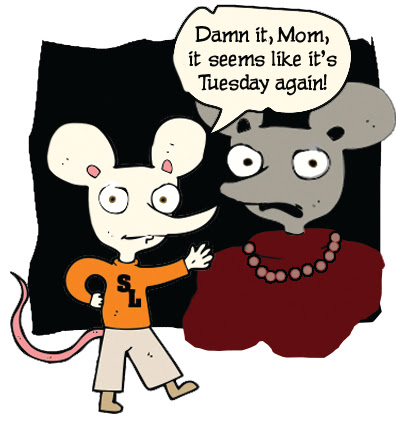

In the final panel, the viewpoint reverses to mother mouse and her child staring toward the viewer. A speech bubble placed over the mouse child’s head reads: Damn it, Mom, it seems like it’s Tuesday again.

The pacing of this eight-panel story is such that it takes time for the reader to comprehend the resignation of the child as he makes a statement about an experience repeated many times before, when his hopes were dashed by his father’s failure to effect a change that would improve life for his mother and himself. The tale’s not humorous, and is not meant to be.

Stewart realized that he wasn’t trying to sell a story or earn money from his efforts. But as each strip evolved, he hoped he’d evoke a response in himself or others that would set him free of the constraining limits that had eroded his outlook on life, and that would shift his direction towards a career better suited to his skills, instead of one that negatively forecast in him a lifetime of hopelessness and failure.

By the New Year, Stewart had amassed a dozen “Mouse” strips that he had shown only to his friend Sharon, whose opinion he respected, as well as his psychology teacher who he’d grown to trust, and who showed a genuine concern for Stewart’s mental state.

Sharon found the cartoons creepy, but then shared them with Brian, whom she was still dating. Brian was very positive about the strip, and told Sharon that Stewart showed great promise. He even asked her to ask Stewart if he could share them with his father, who worked in the editorial department of the Baltimore Sun.

“Stewart’s talent is evident,” said Brian to Sharon. “But at the moment his subconscious seems to be weighing down his abilities, like a nightmare. I hope he can learn to control it.”

Sharon shared Brian’s statement with Stewart, who responded by saying, “I think it’s better for me to express my feelings by drawing and writing cartoons than holding them inside. Somehow, my art has always come through for me, and I may be at the point when I can trust it more than I can trust my own thoughts and the observations of the people closest to me.

“It’s not my mother’s fault... or my dad’s. They both have had a tough life, but I counted on my mother for too long. She was my protector. Maybe my feelings will change. But for now, I have to separate from both of my parents emotionally to survive.”

Stewart met with his psychology teacher in November about his experience at Stein Seal, and told him that although he’d succeeded in relocating the blueprint machine, he felt totally removed from a career in engineering, and was discouraged having to return to another job in the same field. Together, the teacher and Stewart visited the guidance counselor, who offered a suggestion for Stewart. There was a chewing gum factory in Havertown, not far from where Stewart lived in Upper Darby, that needed a person with drafting skills to produce mechanical artwork for stickers and collectibles cards that were packaged with sheets of bubblegum. They currently offered series of trading cards based on World War II and the Green Berets, and novelty baseball cards issued in wax packets. They also had a product called “Swell,” a bubblegum that was twist-wrapped with a cartoon on the reverse side of the wrapper, and a project he might possibly be called upon to participate in the creative process.

Stewart brightened after hearing about a job that would use his skills, and perhaps provide an outlet for his artistic talents. He told the counselor that he was familiar with the Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation, because it was located a stone’s throw from the house he had lived from ages 3 to 4 on Lawrence Road. He told the counselor that while living there, he could never escape the sickening-sweet scent of bubblegum that pervaded the neighborhood.

The guidance counselor set up a meeting for Stewart with the head of the firm, Richard L. Fenimore, Jr., who was the son of the founder. Stewart got together his vellum drawings of mechanical objects created at school, and a couple of the cartoon strips he’d done on his own, and waited to hear back from Fenimore. It wasn’t until mid-January that Stewart got a call and was granted an interview.

By that time, Stewart had completed a dozen of the cartoon strips, and, surprisingly to Stewart, Richard Fenimore was more fascinated by the “Mouse” series than he was interested in his technical drawings from school. Fenimore admitted to Stewart that he was a fan of E. B. White while growing up, and was currently reading Charlotte’s Web to his own daughter, and Stuart Little to his son.

“It was your name that intrigued me when I got the notification from Temple about you possibly accepting a co-op job at our factory,” said Fenimore, and then asked if he could keep Stewart’s cartoon strips to show to others in the firm.

“They are strangely ‘dark’ and truly original,” Fenimore commented as he reviewed the brooding and troubling frames. “We don’t have a need for this here, of course, but your technique might be adapted to other projects we have in the works. And your drafting skills will be useful in our art department, perhaps in creating frames and borders for the multiple series of collectible cards we issue.

“When you’re ready to start, here’s my card, and give me a call. We’ll find a place for you.”

“The drawings I have are the originals,” said Stewart, ” and I haven’t any copies. Will you be sure to get them back to me if I leave them with you?”

“Of course, Stewart. I have connections in a variety of industries. Someone in TV, movies or the press might be interested in this.

“I’m a friend of Mort Drucker, a cartoonist from Mad as well as Don Martin. Maybe they can suggest an outlet for Mouse. After all, no publication out there goes quite as ‘dark’ as Mad.”

-------------------------------------------

The positive response from Richard Fenimore was far more than Stewart had expected, and he was elated over the possibility of securing a job that might match his natural abilities. For the first time in his life he felt that there could be a practical use for his talents, and that he might have a chance to prosper using them despite his mother’s declarations that he should never pursue a career in art.

As he drove home to Upper Darby, he thought of the pathway he’d taken to get to this moment, and the opportunities gained from the hardships he’d experienced. In that moment he could distance himself from his mother’s prejudices and his breakup with Carla. The conflict between the two may have provided the inspiration he needed to express himself, and gain the motivation to aspire towards a goal not possible without the challenges.

He had to chuckle to himself about his name, Stewart Little, which also may have become a key to unlock the door to an interview with Richard Fenimore, and that his alter ego, “mouse,” after all these years, might become transformational as he approached maturity.

No one ingredient in life makes a complete recipe for success, thought Stewart. Every encounter along the way has lead me to this moment. My name, the poverty I endured, the insights of Becky and Sharon, and the dreams, fantasies and abilities of my parents both lost and found have all had an influence on me and have given me this moment. My job now is to be thankful for all of it, and to keep moving forward.

-------------------------------------

When the semester ended in mid-January, Stewart contacted Fenimore, and secured a position in the creative department of The Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation. Fenimore had made sure that Stewart’s “mouse” drawings were returned after showing the panels to Mort Drucker and Don Martin at the Mad offices in New York City. With them, he penned a note of encouragement to Stewart, which he enclosed with the panels:

Dear Stewart,

I was quite impressed with your cartoon strips, and personally took them to New York to meet with members of the Gaines family who publishes Mad magazine, along with members of the staff. The cartoonist Don Martin was particularly taken with both your concept and your style, but the publishers were concerned that the strips were a bit too “cerebral” for their audience. “It’s not funny,” said Mort Drucker, who’s been largely responsible for the parodies of TV shows and movies in Mad since the early ‘50s.

They all agreed that there was a great deal of talent behind the stories you told so simply, and the skills you displayed with your draftsmanship of the panels. Drucker asked your age and your background, and I told him you were 19 and going to school for engineering. “Give him some time,” said Drucker. “Whatever he does, he’ll need to struggle a bit longer. I can’t wait to see what he comes up with in a few years.”

We all acknowledge your gift, but all I can do at this point is provide a job for the upcoming semester. Please contact me when you are ready to start. I look forward to you joining our staff.

One more thing, Stewart. Although I encourage you to develop your talents, I believe that you should finish your studies at Temple, despite the fact that you may not feel comfortable in the program. My advice to anyone is that before one alters an existing direction in life, one should be sure that he or she has a clear view of a path to another. It may be a cliché, but “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.” Instead, work like hell to assure that your plan going forward is solid, and that you have the confidence that you can achieve all that you aspire to.

Will hopefully talk with you soon.

Richard Fenimore

---------------------------------

Will hopefully talk with you soon.

Richard Fenimore

---------------------------------

Comments

Post a Comment