— Chapter Eight: The Strip —

Comedy of Errors may also be purchased from Main Point Books in Wayne,

In the week following his chastisement by Becky and Sharon, Stewart began his quest for self-improvement. He knew that it would take time for him to accomplish his goal of educating himself, but he also needed a short-term solution to attaining a feeling of self-worth, as well as improving his standing in the minds of the two young girls who had questioned his depth and intelligence.

The only talent Stewart knew he had was the skill to draw. Though he hadn’t attended any art classes since elementary school, in his early teens he had mimicked the style of the hot rod artist, “Big Daddy” Ed Roth, in sketches he’d done on the covers of his notebooks and then translated with enamel and brushes to the decks, doors and dashboards of cars owned by kids who liked his style and who hired him to personalize their cars with permanent visual messages, in much the way that past and later generations would use tattoos to establish their own personal identity.

From an early age, Stewart had enjoyed the merging of a storyline with the visual arts, as was successfully accomplished in the DC comic books that he greatly admired, as well as Mad magazine and the “Sunday Funnies,” which appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Despite his appreciation of the medium, he had never thought of creating his own cartoon strip. In searching through his sketchbooks, he found the rough drawings of the “mouse” he’d created for the flyers he’d distributed in his homeroom at the beginning of 10th grade, and which enabled him to rebrand himself from a mouse into “Stewart Little.” He hoped he could succeed in a similar way by using art to change the perceptions of Becky, Sharon and any of the other members of the group who considered him a lightweight thinker, especially Brian, his competitor for Sharon’s praise and her affection.

But Stewart had neither a story to tell, nor a clue as to any direction he could take to quickly effect a change and create an impact in the minds of the girls he valued, but who had different agendas from his own. As much as he disliked probing through card catalogs in the library and the dusty shelves of seldom-read books, he was on a mission, and the library was the only place to turn for past issues of the “Sunday Funnies” and other scripted cartoons.

Unfortunately, during his search he found many of the single-paneled tales to be humorless, but he enjoyed rereading all of the series strips, including Peanuts in which Charles Schultz, the artist and writer of the classic comic, created distinctly different personalities for each of his characters. The strip was drawn in a simple style and featured universally understood stories. He liked Archie Comics, too, and Beetle Bailey, but none he found were consistently great, except Peanuts, which almost always contained a message, and a moral.

Stewart heard Brian talking about V., the debut novel by Thomas Pynchon, a book that was released to much acclaim by critics, including The New York Times. After hearing Brian speak about it, Stewart searched for the book in the school library and, not finding it there, visited the Municipal Library where he found a lone copy. Removing the novel from the pile of “New and Noted” titles, Stewart took it to one of the long tables lit by shaded lights and began to read the first chapter, prefaced by: In which Benny Profane, a schlemiel and human yo-yo, gets to an apocheir.”

Stewart didn’t have a dictionary handy, and already believed himself stupid, so he left his table and walked to the large unabridged dictionary on the stand near the door and looked up the word “apocheir,” but didn’t find it. He continued to read on into the chapter and continued to feel stupid, thinking he lacked the ability to understand the characters, who were vaguely realistic, but who spoke in riddles.

Stewart had often felt confused by books and stories that the teachers recommended, as well as by critics who lavished praise on one author while denigrating another. Most of the books Stewart read were simple stories, and usually were fun to read. Hawaii, though not considered by critics to be great literature, provided the reader with a complex story ranging from the distant past to modern times, and the circumstances faced by natives of the islands as well as the people from far off lands who ventured to the Pacific and settled there.

Although Stewart was enjoying Vidal’s novel Julian, he got lost in the many words he didn’t understand and in the unexplained historic references and characters that were perplexing in their actions. His assumption was that he needed to learn more about the Roman Empire to gain a better understanding of the book, while in the novel V., at least as far as he got that day in the library, there didn’t seem to be any perspective or personal experience that would help clarify the story for him.

Once again, he felt ignorant as he searched through the card catalogue for magazine reviews of V. and found one dating back to 1963, mysteriously titled A Myth of Alligators. It began, In this sort of book, there is no total to arrive at. Nothing makes any waking sense. But it makes a powerful, deeply disturbing dream sense. Nothing in the book seems to have been thrown in arbitrarily, merely to confuse, as is the case when inept authors work at illusion. Pynchon appears to be indulging in the fine, pre-Freudian luxury of dreams dreamt for the dreaming. The book sails with majesty through caverns measureless to man. What does it mean? Who, finally, is V.?

After reading the review, Stewart was more confused by the commentary than he was by the first chapter of the novel, and came to the conclusion that the book was a comic puzzle written for brilliant people to make other people feel stupid. Stewart’s opinion was confirmed by a reviewer in a later publication who stated: His (Pynchon’s) goal is to make you feel dumb, and if you read one of his books and tell yourself that you understood it completely the first time (or the second, or the third) then that, in my opinion, is a worse sign than simple befuddlement by his works.

Whether knowledgeable about fiction, or a novice, Stewart had gained some street smarts in dealing with people, and had learned something from his encounters with most of those he met, as well as by every circumstance by which he was challenged. He admitted he knew little about classical music and poetry, and was aware that there were some of each he liked and could relate to, and others he didn’t care for. His opinion was occasionally changed as he grew to learn more about a subject, but it mostly remained consistent, as did his knowledge of right and wrong. He could trick himself into believing, or admit that he was at a loss when discussing subjects beyond his understanding, but his values remained integral to who he was.

Despite its complexities and vagaries, V. stuck with him, as did Pynchon and later Thomas Wolfe, both of whom were declared geniuses by some, and fools by others.

After reading only one chapter of V. and the two reviews, Stewart decided to take a chance and attempt to interpret, in a cartoon strip, the various benefits people get from reading books, based on his knowledge of people.

In panel one, he drew a child with a book with the words “Stuart Little” on the cover. The cartoon depicted a small boy hunched over the book, which he was clasping tightly, and smiling. His eyes were open wide with wonder.

For panel two, Stewart drew a woman in a long-buttoned suit with a high collar and tight hair, over which appeared floating hearts. Her head was thrown back in a swoon and her eyes were half shut. One hand held the book which revealed the title, Jane Eyre, on the cover. The back of her other hand was resting against her forehead.

Panel three featured an older man wearing glasses with an open book close to his face and his eyes squinting, but intent on the page. His left hand held the book while the thumb and forefinger of his right hand were poised to turn the page. The Ipcress File was printed boldly on the cover.

Panel four showed a woman holding a tall drink in her right hand with a parasol sticking out of the glass. She wore glasses that ended in points that extended beyond the corners of her eyes, and a bathing suit that came down low on her chest, with the straps of the suit untied and hanging to her side. The cover of the book showed the title, Hawaii,written in large bold serif letters.

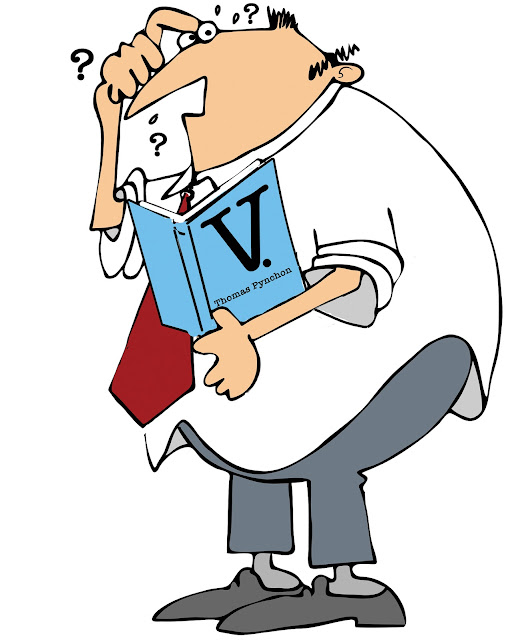

The final panel, number five, portrayed an overweight man in an untucked white shirt who’s scratching his head and perspiring profusely. He appeared confused, as question marks circle his skull. The book he’s reading is titled V. and below the title is the author’s name: Thomas Pynchon.

Stewart drew each of the cartoons separately on vellum and colored them with markers that his mother had brought home from work. After completing them, he mounted each on foamboard, cut them to the same size and glued them to a black mat background. With a fine-point silver marker, he titled the strip, The Readers, and brought it with him to Fellowship the next Sunday night. The panel was covered by a flap so no one could see the strip prior to the meeting.

Surprisingly, Brian, who only showed up occasionally, was there for the gathering, and already in a discussion with Sharon, Becky and Bob on the subject of politics and the Vietnam conflict. The vestry had recently appointed Tom Strong, a science teacher at Upper Darby High, and Janet Davis, a civic leader, parent and an elected member of the vestry, to the advisory positions. Neither of the leaders was very familiar with the group, and both used the business part of the meeting to acquaint themselves with the members. During “sharing time,” as the advisors called it, each member was asked to address a social issue or concern that had affected them since the previous meeting, or a topic that they thought would be of interest to the group.

When it was Stewart’s turn to share, he explained that he’d been motivated by members of the group to read more and expand his range of interests.

“Based on what I learned about myself, I decided to make some positive changes, and to use the skills I have to better convey my thoughts than I was able to do with spoken words.”

He lifted the board from his side and folded back the cover flap, passing it to Ronnie, who was seated to his left. She knew that Stewart’s mother was an artist and asked him if she had created the drawings. Stewart told her that he did them on his own.

“But you don’t take art in school, Stewart. Did she help you with this?” “No!” he answered emphatically. “She doesn’t even know I did it.”

The entire group grew interested as Ronnie held on to the board a bit too long as the other members asked to see it. She turned it around and revealed the cartoon strip to the group while asking Stewart what it meant, and why he had done it.

She then passed it to her left, and when it got to Becky, she paused at each panel, and looked up at Stewart, amazed by his artistry, but also by his visual explanation noted by the hand-printed title: “The Readers.” The board soon reached Sharon who was seated next to Brian, and she, too, was surprised to see how he’d interpreted their conversation the previous week. She then passed the board to Brian, who made a comment about his reasons for Stewart’s use of the book V. for the final panel.

“Nice job, Stewart. Have you read all of these books?” asked Brian.

“Most, but I’m familiar with them all,” answered Stewart.

“What was your purpose in doing this?” questioned Brian.

“I thought I could use it to better understand and express myself,” he answered.

“It’s interesting – your choice of books and people, and who you use as your readers,” Brian added as he passed the board to his left for another to see.

When the panel got to the advisors, they both studied it for some time before commenting. Stewart saw that Brian was watching him and also the group’s response, which by their expressions varied from member to member.

What surprised Becky and Sharon was the speed at which Stewart had apparently worked at what they thought was his first attempt at cartooning, and the expertise he showed in matching the books to the characters.

Stewart wasn’t blind to the reaction he got from them, as Tom Strong asked about what provoked this “beautifully executed” piece of work.

Stewart thought about it and answered, “Sometimes people don’t know that I pay attention — but I do, a lot more than they think I do. Like the child in the first panel, I got a sense of joy when reading as a young boy, and listening to my mother read me children’s books. Of course, the story of Stuart Little, being similar to my own name, has caused me problems in the past, since I share my name with that of a mouse.

“The lady wearing the tan suit is a caricature of Miss Conklin, the school librarian. I know, from listening to her, that although she looks very prim and proper, she has a romantic side, and I’ve seen her reading romance novels, which she hides when students enter the library unexpectedly.

“My father enjoys mysteries and stories about espionage during World War II. He was stationed in the Pacific. He also likes to escape into a fantasy world of intrigue. I like Ian Fleming’s Bond series because, even though I’d love to drink martinis, drive fast cars and enjoy the company of beautiful women, I’ll never have the chance or courage to become a secret agent.

“I read the book Hawaii in the ninth grade, and although it was long, I really learned a lot from it. Some people may think Michener’s not a literary writer, but what he’s accomplished is making it easy for his readers to learn about the cultures and enjoy history, whether lying on the beach or by looking forward to picking up the book again before they go to sleep at night.

“The book that motivated me to create the strip was V., which is quite long and complicated and, from what I discovered, was written by a novice writer. I never heard about the book until I heard Brian talking about it and praising it, a couple of weeks ago. I couldn’t find it in the school library, so I went to the Municipal Library to find it. I read the first chapter, then skimmed through the book, and wondered why it seemed to arouse great praise, and so much interest, from Brian.

“While at the library, I researched opinions of critics, and I realized that they weren’t sure whether it was a great book, or if it was a joke, and I came to the conclusion that, overall, the act of reading is valuable for everyone, and that some people like books that are puzzling, while others like novels that allow them to escape into their own imagination, and still others carry with them the stories of childhood and help them find their way through life by the situations experienced by characters they idolized when young.”

The members of the Fellowship had never heard Stewart speak in this manner, or this long, on any subject.

“You must enjoy reading a lot, Stewart,” said Mrs. Davis.

“I do like books, but I like a lot of other things too, like cars, model trains, and popular music.”

“But you must also enjoy drawing. You’re remarkably good at it,” responded Mr. Strong.

“Drawing’s okay, but I don’t think art’s for me.”

“What does your art teacher say about your skill?”

“I don’t take art,” said Stewart. “At least not since the 6th grade.”

Mr. Strong appeared bewildered and looked over to his co-advisor, who addressed Stewart as if he were the only person in the room. “You know that you have talent, Stewart?”

“I guess I do, but my mother’s been an artist her whole life and we can barely afford our rent some months. My father draws postcards all day long and doesn’t make a cent.

“I don’t want to end up that way, and hope I can find something else I’m good at.”

Becky and Sharon had been exchanging glances throughout Stewart’s conversation with the advisors, and Becky raised her hand to speak.

“Yes, Becky,” said Mrs. Davis, pointing to her seated directly across from her in the circle.

“I just wanted to say that I believe that Stewart will be great at whatever he chooses to do.”

The meeting ended with a small group, including Becky and Sharon, gathered around Stewart and his cartoon. Becky asked if she could borrow it to show her parents and her brothers. Sharon took Stewart aside and told him how proud she was of him, and with a smile and a gentle shove, said “Gees, Stewart, when and how did you get so smart — since last week?”

Brian waited until everyone was preparing to leave, and caught up to Stewart as he was getting into his coat.

“You know that you’re probably right about V., Stewart, but I did enjoy it a lot.

“It’s a bit of a joke on life, and the humor is often confusing and quirky. You also did a really good job with your cartoon strip. I wish I could draw, but that’s not a skill I have. I’m a bit envious of your talent. I hope you can put it to good use. I’m still not sure what direction I’ll take in life. I haven’t applied to any colleges, and don’t have a plan. So I guess we both should lighten up a little and enjoy the time we have.”

Stewart was surprised and pleased by Brian’s response, as well as the praise of the other members of the group and the advisors. He knew that he still had a lot to learn, but was also beginning to realize that understanding people and caring about their feelings and motivations is a gift that may be much greater than any single talent. And that it might be possible, like Charles Schultz did, to combine skills and talents to make a living as well as to attain riches that can be much greater than fame or fortune.

----------------------------------

Comments

Post a Comment